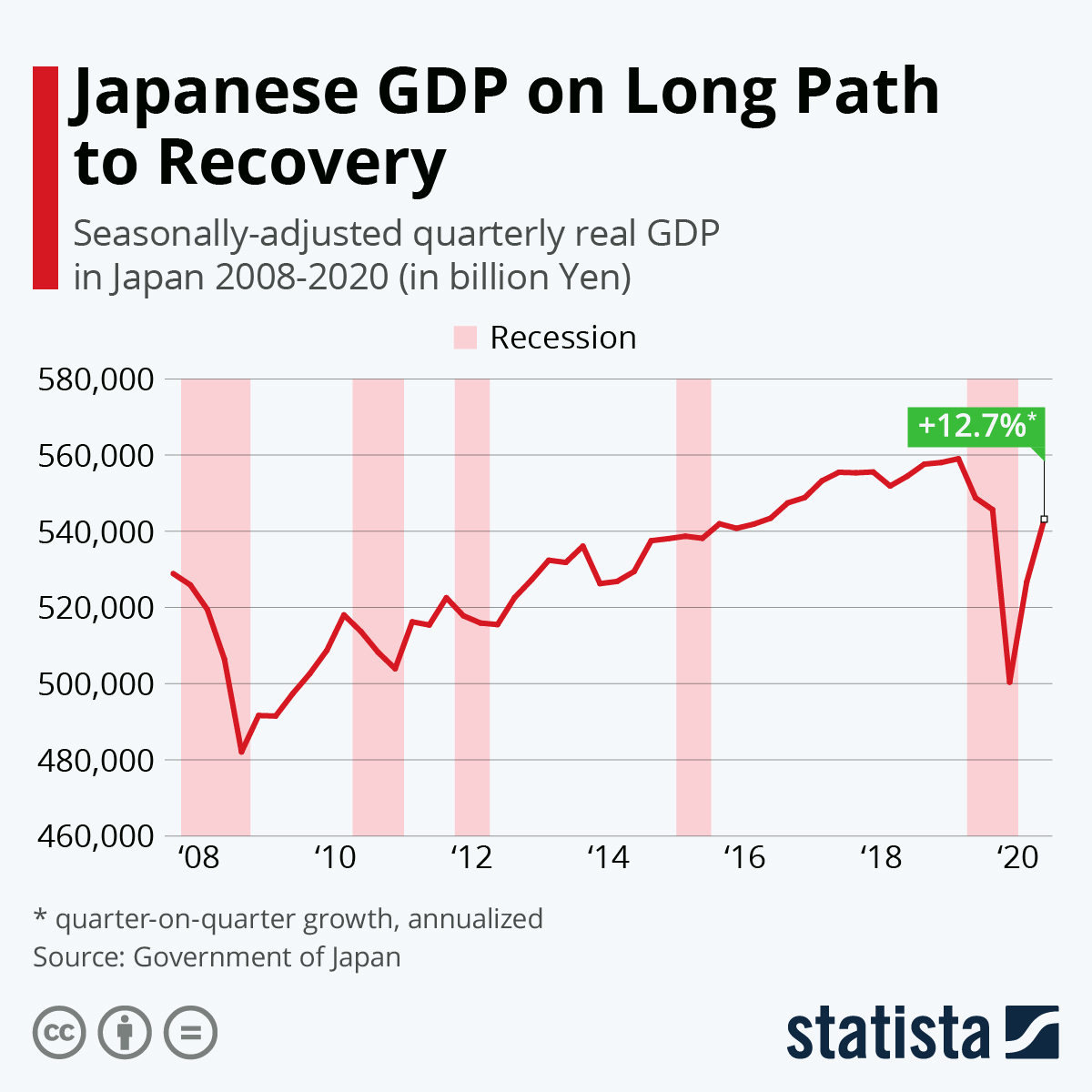

Japan. the world's third-largest economy is highly dependent on exports and the reality it is still struggling even after a great deal of America's stimulus money leaked into buying imported goods speaks volumes. While it feels a bit like ancient history, Japan's GDP contracted at an annualized rate of 28.8 percent in Q2 of 2020, the biggest decline on record. Even after bouncing back 21.4 percent quarter-on-quarter in Q3 and 12.7 percent in Q4 Japanese national accounts are still lagging behind mid-2019 levels. For all of 2020, spending by households with at least two people fell 5.3% due to the hit from the pandemic. It was down 6.5% for all households, the worst drop since comparable data became available in 2001.

|

| https://cdn.statcdn.com/Infographic/images/normal/22583.jpeg |

Not only is Japan again struggling to stay out of recession, but it also faces a wall of debt that can only be addressed by printing more money and debasing its currency. This means they will be paying off their debt with worthless yen where possible and in many cases defaulting on the promises they have made. Japan currently has a debt/GDP ratio of about 240% which is the highest in the industrialized world. With the government financing almost 40 percent of its annual budget through debt it becomes easy to draw comparisons between Greece and Japan.

Over the

years Japan has been able to sidestep default due to the good fortune of

sporting a huge trade surplus with America and forming tight economic

ties with China during the years it was rapidly growing. Unfortunately,

for Japan, the benefit of both those forces may be waning. China has moved up the manufacturing chain and no longer needs Japan as much as it did. This leaves Japan in the unenvious position of having to find new ways to move forward at a time when few friendly trends have surfaced to aid in its endeavor.

The Japanese economy has been no stranger to recessions even before the coronavirus outbreak. In fact, Japan experienced three mild recessions between the COVID-19 pandemic and the global financial crisis. The first was caused by the devastating earthquake and tsunami that rocked Japan in 2011. The other two and single negative growth quarters appeared to be just part of the long stagnation the Japanese economy has been in since its asset price bubble burst in the 1990s.

In the aftermath of the crisis, Japan amassed a mountain of debt that it carries to this day. Japan's aging population and shrinking consumer market have made it hard to revive the Japanese economy. The country’s continued reliance on exports and tendency to invest overseas

rather than at home have become a big part of what Japan does. For years the now-former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe promised the

country relief through his “Abenomics” economic revival program but

it never did lift the country out of stagnation.

The Abe administration

significantly eased monetary policy and increased government spending,

while simultaneously talking about needed structural reforms most of which always seemed to be pushed back or get delayed.

|

| Japan's GDP Is Flat Since 1990 click to enlarge |

Not all economists see more deficit spending as the answer to Japan's

problems and argue that more spending will only hurt efforts such

as the recent consumption tax hike to improve Japan's overall fiscal

health. Japan holds the title of having the industrial world’s

heaviest public debt burden. Its debt is more than twice the size of its

$5 trillion economy.

The world's negative-yielding debt hit a record $17 trillion at the

start of September, mostly as a result of most Japanese debt trading in

negative territory as the Bank Of Japan continues to monetize the

country's debt. All this also flows into Japan's stock market where, when we see Japanese shares rise we are now forced to wonder how much of it has to do with Kuroda and the BOJ pumping up Japan's stock market by buying more ETFs. It is difficult to argue that in effect, the BOJ buying stock is not nationalizing Japanese companies.

|

| The BOJ Owns Nearly 80% Of Japan's ETFs |

What we see occurring in Japan stems from a far greater problem than simply slow growth. At some point, reality will set in and the yen will suffer as a result of Japanese policies. For many years Japan's relationship with China has bolstered the yen. The collapse of the yen would debunk the myth that major currencies in our modern world are immune to failure and release a slew of new problems across the world. While this has been expected for some time it most likely will not be the catalyst for global financial collapse since the yen constitutes around only 4% of the world's reserve currency, however, it would gravely wound fiat currencies and alter how they are viewed.

Factoring into all of this, in September of 2020, Yoshihide Suga, became Japan’s new prime minister. Suga took over from 65-year-old Shinzo Abe, the country’s longest-serving prime minister, who resigned due to health reasons. On the domestic stage, Suga inherits a troubled agenda swamped by the coronavirus pandemic, he also has to deal with the disaster of the postponed Tokyo Olympics. As the leader of one of America’s closest allies he also has to navigate a tense geopolitical climate resulting from the rapidly deteriorating U.S.-China relations and the idea Japan wants the U.S. to deter China’s military aggression in Asia.”

Borrowing a huge part of a nation's economic output every year to prop up the status quo is akin to putting a Band-Aid over a wound, that in this case, is rapidly growing larger. In short, Japan's flawed prescription for future growth will never work. Many of the policies that have failed in Japan over the decades are now being played out across the world. Interestingly, over time, the "Japanification" of the world's economy may play out far worse for the global financial system than it did for Japan.

Republishing this article is permitted with reference to Bruce Wilds/AdvancingTime Blog

No comments:

Post a Comment